Without turning this into a lesson of history or a commentary on religion, permit me to capsulate a mixture of both, employing a bit of literary license to contain it within a reasonable length.

The Man from Galilee sent forth His disciples to spread His gospel of love and peace, having named Peter as the foundation stone, the rock, upon which He would build His Church (Matt 16:18). Peter did not have an easy time of his mission, and like his Master, was crucified, but upside-down. Peter’s successors continued to strive, and slowly the difficulties began to ease, and the Church grew, and their stature, the stature of the Pope, increased.

By the end of the first millennium, the position of the Pope equaled that of most monarchs. He had become a man of great institutional wealth, ruling over vast tracts of land and the peoples thereon. He was a power in politics. This reached a peak during the tenure of Hildebrand, Pope Gregory VII (1073-85), a small, visually and audibly unimpressive man, but with great intellect and power of will. By 1075 he had established, then executed and enforced absolute and total Papal supremacy. He took to the Pope the right to dispose all «princes,» (kings, emperors, dukes, cardinals and lesser) temporal and spiritual. All Christians were subject to the Pope. Kings and Emperors required his blessing before they could take office. The Pope was now supreme! All religious matters, all political matters, all matters, were subject to the determination of the Pope. This was the pinnacle to which successive Popes had striven for a thousand years. However, this happy state did not persist. Gregory’s successors were unable to hold his ground, for the

Christian rulers were not willing to let so much power remain out of their hands. Temporal nobles began to defy Papal requirements; Church nobles — cardinals, bishops, even priests, sought a more rewarding life, with authority and influence for themselves. The disintegration, or perhaps revolt, became so great that the Papal See was relocated to France for over 70 years, and for the second time in its history, the Church had two Popes and, for a time, three!

The remaining supremacy of the Church, as well as the power and prestige of the Pope suffered a mighty blow in the 16th century when Martin Luther, a German monk-priest, identified what were, to him, critical differences in the interpretation of the Gospel, and he could not reconcile the simony and avarice in the Church — such practices as selling absolutions and Church positions. Thus was born Protestantism, the most severe and lasting threat the Church had encountered.

Political dissatisfaction, political activism, to put a modern term to an old practice, and political plotting had become widespread. Political leaders, and this included kings, became targets of dissent and the subjects of plots at several levels. Spying and tale- bearing became commonplace.

It was this general atmosphere as well as a growing awareness of self among the people that fostered «secret societies,» several with initiations, passwords, vows of secrecy and severe punishments for disclosing happenings within the group. Such groups, generally politically-oriented, developed throughout Europe and in to England. It could well be that this atmosphere played a part, perhaps unconsciously, in the development of the Premier Grand Lodge in London in 1717, not as a cover for plotting and scheming, but as a refuge from it!

By this time the territorial domain of the Pope had eroded to a wide band across the Italian peninsular from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic, from south of Rome to well up the coast, across and up the Adriatic coast nearly to Venice, comprising about 20% to

25% of the Italian «boot.» Protestantism was growing and spreading widely and rapidly; Roman Catholic adherents were decreasing more speedily than new converts were being made.

In just a few years following 1717, Freemasonry crossed the Channel from England to several areas of Europe, spreading to France, Germany, Italy, Holland. A lodge was founded in Florence in 1733.

The Pope had an office, a position, an institution, a Church, sponsored by the Almighty, given by His Son into the hands of a succession of holy men, men who, with their adherents, their corps of believers, their army of the faithful, had fought for a thousand years to build into the most significant and powerful force for good on Earth. And now, while beset by the sniping of mere men, pulled at and shrunken by the politics of the time and the breakaway Protestants following Luther’s lead, there arose from the masses a new element — or perhaps an old element with a new face, a sect calling themselves Freemasons, a group with solemn secrets, a group which would not divulge to their confessors what these secrets were, what plotting was conducted behind their closed and guarded doors!

Here was a new or a reinvigorated enemy, rising rapidly, an enemy to be contained and combated as best as could be done! Prosecute them; isolate them; arouse the good Christians to beware of and keep clear of them!

With this background, is it any wonder that the Papal Office utilized its most potent threat of punishment, excommunication? [Death, although sometimes occurring, especially with the Inquisition, was not accomplished as a punishment per se.) A Papal Bull was issued, the Bull In Eminence.

This was the first of the Papal Bulls, an expression I shall employ herein only to those documents, whatever their nature or correct name, if wholly or partially inimicable to Masonry.

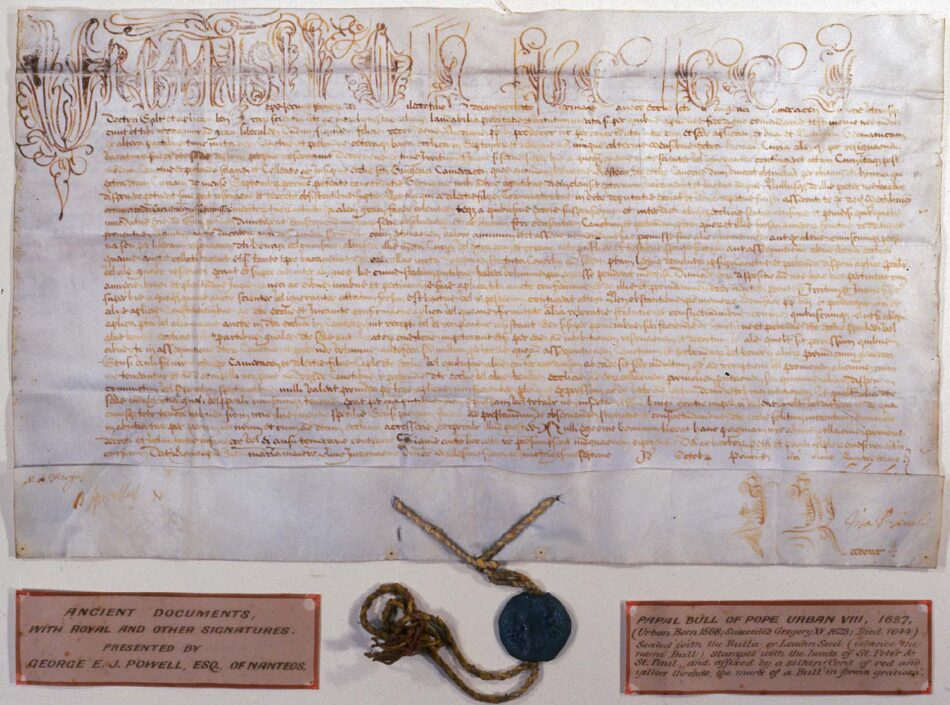

Firstly, now that the term has appeared, what is a «Bull?» It, or they, are ecclesiastical pronouncements of considerable weight promulgated by or in the name of the Pope of Rome, and written in Latin. However, there is no document title of bull. The documents may by their nature be «constitutions,» «decrees,» «declarations,» or «encyclicals.» The term bull derived from the Latin «bulla» or seal, and refers to the metal (lead for pontifical documents) blob in which the hempen or silk binding of the document was embedded, with the imprint of a signet or seal impressed on it. Although having previously been employed in royal and imperial courts, sometimes with gold bullas, usage from approximately the 12th century appears to have been limited to papal documents.

And at about that time they became standardized with an impression of the likeness of Saints Peter and Paul on one side, and the signature of the issuing Pope on the other. Somewhat later the signature was changed to a likeness of that Pope. Yet further on, the lead bulla was replaced by a red stamp and impression, much as lodge seals.

How many Papal Bulls are/were there? I do not know. Sorry. Some writers say 12, some more, up to «approximately 20.» There is no listing I could find of «Papal Bulls against Masonry,» nor could I find a book of all papal documents in translation —not that I’m really ready for that yet. I have about 14 in English, a couple more in Latin, and a few more identified as probables, but not yet in hand. So, I’ll go along with the «about 20.» Not all are real hair raisers about Masonry. One identifies the subject as Masonry by inference, then mentions another pet peeve of the Papacy, the Carbonari. What they say would take a couple of hundred pages, if I had them all. Let me point up some of what the first one says, a bit of the «big one» and perhaps a few words on a couple of others.

The first, In Eminente, was published by Pope Clement II on, as before stated, April 28, 1738. [Permit me to digress to discuss the authorship of this document: Our most excellent secretary —and it’s hard to try to do justice to a Mason as I tried there, without using words taken as a Masonic title somewhere; I am not trying to call Right Worshipful Brother Allen E. Roberts a Past District Deputy Grand High Priest, just a good man, a good Mason, and a good Lodge Secretary. But to continue, Brother Roberts, in his revisions to Coil’s Masonic Encyclopedia, includes the likelihood that Clement not only did not write or sign the document, but may not have been cognizant of its existence. This is quite possible; Clement was an old man, for those days, 78, when, in 1730, after 4 months, the conclave of cardinals – selected him as Pope. Suffering from physical ailments, including severe gout, two years later he became blind. In a not uncommon example of nepotism, he had early on elevated his nephew, Neri Corsini, to the rank of cardinal, and with the blood connection his prime qualification, Hen did much of his uncle’s work, quite likely including this Bull, a document that started the series which has disrupted relations between the great Roman Catholic Church and the great fraternity of Freemasonry. However, it must be noted that staff work accomplishes much of what any extremely busy personage produces.]

In Eminente commences: «The Condemnation of the Societies or Converuicles De Liberi Muratori, or of the Freemasons, under the penalty of ipso facto Excommunication, the Absolution from which is reserved to the Pope alone, except at the point of death . . .» and continues in paraphrase: It has come to our knowledge, even publicly, that societies of Freemasons, spread far and wide and every day increasing, confederate together in a close bond according to laws agreed upon between themselves, and with private ceremonies bind themselves by strict oath taken upon the Bible and by imprecations of heavy punishment to preserve inviolable secrecy. We do condemn and proscribe these societies, companies, clubs, conventicles, De Liberi Muratore or Freemasons, or by whatever other name they may be distinguished or known.

«We strictly commend that no one under any pretext promote, favor, admit or conceal in his or their house or elsewhere, or be admitted members of or be present with the same etc., etc. under penalty of excommunication ipso facto.» (All this in quite a few more words.)

The next Bull, Providas (May 18, 1751) by Pope Benedict XIV confirms the earlier one, quoted it en toto, and added much more. He set forth six specific causes for condemning the Freemasons, as follows:

- That men of every religion and sect are associated together, from which it is obvious how great an injury could be inflicted on the purity of the Catholic Church.

- The closer and impenetrable bond of secrecy by which their proceedings are kept hidden.

- The oaths by which members vow secrecy, claiming that this vow protects them from being bound to confess, when questioned by legitimate authority, of anything contrary to religion, the state and the law.

- Societies of this sort are known to be in opposition to civil as well as canonical sanctions.

- Already, in many places, these societies and meetings have been banned by local laws.

- These societies are of ill repute among wise and virtuous men, and in their judgement, all who join them wear the brand of depravity and perversion.

The next Bull to show was Eccliesiam by Pope Pius VII on September 13, 1821, berating societies which do all sorts of bad things — including being ravenous wolves in sheep’s clothes.

He identifies these societies throughout as the Carbonari, except in the middle of the document where it acknowledges the example of Clement in In Eminence and Benedict

in Pravidas by condemning and prohibiting the Societas De Liberi Muratori, or Freemasonry or «by whatever name called», an offspring of which this society of Carbonari must be considered.

Following was Quo Graviora promulgated by Pope Leo XII on March 13, 1825. Although the leaders of the Carbonari were put on trial in 1821-22, they were included in the condemnation, which included verbatim the first three Bulls against Masonry, in all amounting to about sixteen close-typed pages.

There follow several others, including Pius VIII’s Traditi Humilitati of May 24, 1829, which is the presentation of a new Pope’s program for his Pontificate, including mention of the preceding Bulls against Secret Societies, and his pledge to strenuously take up the mission of destroying the strongholds which the putrid impiety of evil men set up, and Gregory XVI’s Mirari Vos (August 15, 1832), denouncing notions of freedom of conscience and the press, and separation of Church and State.

Pope Pius XI’s Qui Pluribus of November 9, 1846, set forth his programs, announced his fight against heresy and confirmed the anti-Masonic Bulls of his predecessors. His Quanta Cura of 18 years later, again recalled and re-confirmed these Bulls. The following year his Multiplices Inter laid into our Fraternity, heavily denigrating and condemning it, likening us to wolves in sheep’s clothing, placing us among the number of those whose society has been forbidden to Catholics, «eloquently prohibiting [them] from even saying to [us] — Hail!»

Pius IX had time (1846-78) for more, but only of minor import. Following him was Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903), a great Bull-writer, with at least seven anti-Masonic Bulls to his credit (?). Crowned at age 68 and in frail health, his was considered a popular but stop- gap selection. He ruled, though, with a masterly flair, making a sharp break with some of Pius IX’s policies, but continuing and intensifying others.

Humanum Genus, his second Bull under my adopted definition, was the most accusatory and denunciatory of all. It says, to paraphrase a loose translation:

The human race, after departing from God, divided itself into two different and opposing factors, one of which assiduously fights for truth and virtue, the other for things these oppose. The one is the Kingdom of God on earth — the Church of Jesus Christ and those who for their salvation serve God and His only begotten Son with their whole mind and their whole will. The other factor is the kingdom of Satan, in whose power are all who have followed his sad example and that of our first parents. The one fights the other with different kinds of weapons, and battles at all times, though not always with the same ardor and fury. In our days those who follow the evil one conspire and strive together under the guidance and with the help of that society of men spread all over and solidly established, which they call Freemasons.

So there we have it: Them or Us. No middle ground. One side led by God and the Pope; the other side led by Freemasons for Satan. It claims that we have executed some who have betrayed our secrets or disobeyed an order, so skillfully that the murderer escaped the investigation of the police. He states that we are not in agreement with honesty. He trots out the old complaints of naturalism, of striving for the full separation of the Church from the State, accuses us of waging war against the Apostolic See and the Roman Pontiff, under false pretense depriving the Pope of temporal power, of the stronghold of his rights and his freedom, of reducing him to an iniquitous condition, and it goes on and on and on.

I recommend the reading of this document to all Masons, that they may see us as the Catholic Church sees us — and I commend it doubly to those of us who are Roman Catholics. It was printed by the Southern Jurisdiction of the Scottish Rite in 1884 with some excellent commentaries by then-Sovereign Grand Commander Albert Pike, and re- printed in 1972. It may be found by those lucky enough to have or be able to borrow a

copy, as appendices D, E and F of Al Cerza’s book Anti Masonry, or without Pike’s responses, in our last speaker, John Robinson’s Born in Blood.

I will not go into any of the various responses made to the several Bulls. There is a myth that Masons do not «strike back», do not respond to any of the various sticks and stones thrown at us. Not really so, as III. Brother Pike’s will show, and as do several others, before and after.

There were a number of Bulls still to follow, five more by Leo XIII, I believe, but none to equal Humanum Genus. A word of explanation, or at least, of connection, may be due in conjunction with the Pope’s complaint that the Freemasons had placed him in an iniquitous position: earlier I gave the Pope’s temporal empire as about one-fifth of the Italian boot in 1717.

Things did not remain static; the Risorgamento, or reunification of Italy into a nation, led by three Italian heroes, Giuseppe Mazzini, Giuseppe Garibaldi, and Count Camillo Benso di Cavour, all staunch Masons, earned for themselves the Pope’s considerable animosity, and added to his hatred of Masonry. His sovereign territory had been reduced to the Vatican and Lateran Palaces and, outside Rome, the Castle Gandolfo — in all, about 103 acres!

The last of Leo’s anti-Masonic Bulls was Annum Ingressi of March 18, 1902, its significance being that it was the last. Was there nothing more? There was. Leo’s successor, Pius X (1903-14), introduced several innovations, one of which was the codification of Canon Law. He put this task in the hands of a University Commission, and although nearly complete at the time of his death, it was not published and enacted until 1917, 3 years after his death. This codification contained all the laws considered needful for the running of the Church, ordered in a way easier to find. However, the old documents, such as the anti-Masonic Bulls, were not canceled.

Cannon 2335 stated: Persons who have themselves enrolled in the Masonic sect or in other institutions of the same kind, which plot against the Church or the legitimate civil powers, were ipso facto excommunicated, reserved simply to the Apostolic See.

This seemed to ease up on the offense; the «which plot» and «reserved simply» lowered the offense from a «most heinous» crime to one of considerably lesser severity.

I need to digress again to state that Freemasonry as we know it is not necessarily the Freemasonry found everywhere. Many Masonic bodies in Europe, especially France and Italy, in the 18th and 19th centuries were politically infested. The Grand Orient of France and subordinate lodges are not recognized by most jurisdictions we consider «regular»; we do recognize the Grande Loge National Francaise. There were, and are, several Grand bodies, mostly Grand Orients, similarly not recognized, mostly because they did not require a belief in God or our equivalent wording and/or did not preclude discussion of religion or politics in Lodge. To the Papal See, these distinctions were not significant; all were considered Freemasons.

Many Masons and some well-positioned Catholics interpreted the phrase «which plot against the Church» as permitting, at least passively, Catholics to be or become members of British or American Masonry. The Scandinavian (Catholic) Conference in 1967 opined that the bishops of these countries could permit Masons of their countries to become Catholics without renouncing Masonic membership.

In 1971, the Dean of the Faculty of Canon Law at the Gregorian University in Rome declared that joining a lodge which was neither sectarian nor anti-church could not be subject to sanction in terms of ecclesiastical law.

A Vatican document dated 19 July 1974 authored by the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (successor to the Inquisition) and signed by its Prefect, Cardinal Semper (and known in some circles as the «Semper Document»), answered the questions

put to it by many Bishops concerning the effect on Canon 2335. Its response was that the general statutes remained in force, but in considering particular cases, one can follow the opinion that 2335 affects only those Catholics who are members of associations which do not conspire against the Church.

Catholics who had left the Church to become Freemasons were urged to seek reconciliation. Priests and the like were still prohibited from membership.

On 27 November 1983, the Code of Canon Law was revised and republished, with new numbering and new wording. Whereas Freemasonry had been specified in the 1917 Code, the 1983 version, effective 27 November, does not mention the Fraternity either by name or context. The Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith was again asked to define the position on regular Masonry. Their answer follows, dated the day before the new Code became effective.

Declaration on Masonic Associations

It has been asked whether there has been any change in the Church’s decision in regard to Masonic associations since the new Code of Canon Law does not mention them expressly, unlike the previous Code.

This sacred congregation is in a position to reply that this circumstance is due to an editorial criterion which was followed also in the case of other associations likewise unmentioned inasmuch as they are contained in wider categories.

Therefore, the Church’s negative judgment in regard to Masonic associations remains unchanged since their principles have always been considered irreconcilable with the doctrine of the Church and, therefore, membership in them remains forbidden. The faithful who enroll in Masonic associations are in a state of grave sin and may not receive Holy Communion.

It is not within the competence of local ecclesiastical authorities to give a judgement on the nature of Masonic associations which would imply a derogation from what has been decided above, and this in line with the declaration of this sacred congregation issued Feb. 17, 1981.

In an audience granted to the undersigned cardinal prefect, the Supreme Pontiff John Paul II approved and ordered the publication of this declaration which had been decided in an ordinary meeting of this sacred congregation.

Rome, from the Office of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Nov. 26, 1983.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger Prefect

This would seem to return the status to, if not square one, not quite all the way on square two, maintaining the confusion. A year later, the Vatican’s newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, reported many enquiries without response at first, but eventually inconclusive, indirect and elusive response was given. The Ratzinger document was termed a retrograde step. Masonry was reported as no longer plotting against the Church, but its original principles and doctrine had not changed, and that while Catholics who join Masonry are not excommunicated ipso facto, such membership constitutes a grave sin, and they are precluded from participating in Holy Communion.

Regrettably, the matter is not yet resolved. Catholics ARE in Masonry. In 1955, when I petitioned a Lodge in New York, the Master was a Catholic, as were two of the three men who investigated me. I got in line, and when I was senior deacon, the Junior Deacon was Catholic. When I transferred out (military), he moved up to Senior Deacon. I have since sat in lodge with many Catholics, participated in conferring degrees upon them, and have recommended some for the degrees. These men were excellent, and we could use many

more like them. I have always recommended to a Catholic who was petitioning, or about to receive his degrees, that there existed some strain between the Catholic Church and our Fraternity, and that before going further he should discuss the matter with his parish priest.

I have presented this paper neither as an apologia for nor a condemnation of, the included Popes or the Roman Catholic Church, but rather to lay before you some — just some, of the Church’s actions as regards Freemasonry.

The possible influences I set forth may have had no bearing; the thinking I attribute to these men may be wholly inaccurate. I shall learn more about the Papal Bulls; I am fascinated. For instance, I must learn more about the Pope who, reportedly and with some convincing evidence, was a Freemason. I could have expanded considerably on many of the subjects included, but I am sure that this is sufficient for the occasion. I thank you.

Herbert M. Hartlove

Virginia Research Lodge No. 1777

December 14, 1991